One of my mantras is that doing economics is not about “being right,” but about getting wiser all the times. Note that the two things may not overlap. I, for example, would rather be wrong all of the time but know why I am being wrong instead of being right without having a clue as to why. So, I think it is a good mantra, and I will stick with it. Now, after the beginning of the current financial crisis and recession, more or less prominent economists lined up to tell the world that they were “right” as they had seen the crisis coming. Some actually had something to back up their claims with, whereas most had cried wolf for years and were just bound to get lucky.

Here, during the Holidays, I take the liberty of deviating from the mantra and submit myself to those who claim to “be right” about something. The “something” is the current debt crisis in Europe. A paper I wrote (with Roel Beetsma, University of Amsterdam) a long time ago, actually predicts that when heterogeneous countries form a monetary union they will diverge in terms of structural performance from each other. Interpreting structural performance in a fiscal dimension, it predicted that debt and deficits would diverge after unification. This would be in contrast to a form of unification that can easily be undone (“reversible” unification), say, a fixed exchange rate regime like the EMS. Under such a regime there would be no structural divergence. But in a regime that is hard to undo—in the paper literally impossible (“irreversible” unification)—divergence will be the result, as is currently the sad case in reality.

I humbly note that this captures important facts of European monetary history of the last 30 years. The paper is Roel M.W.J. Beetsma and Henrik Jensen (2003): Structural convergence under reversible and irreversible monetary unification, Journal of International Money and Finance 22, 417–439. The first draft was circulated in August 1998, and I presented it during 1999 (just at the time of the formation of the Euro; without the Euro currency). The polite commentators said it was a nice technical exercise with little relation to the real world. The more critical commentators said it was a silly exercise with no relation to the real world. One of the features that was considered unrealistic, I think, was that we used a Barro and Gordon (1983, Journal of Political Economy) credibility model as a foundation for our framework. That sort of model was out of fashion at the times (as most apparently thought that all policymakers acted as under commitment, or that credibility problems were an issue of the past).

Well, the basic mechanisms of the model are simple. a) Structural problems (unemployment, too high debt, etc.) leads to credibility problems in monetary policy; b) Credibility problems leads to inflation; c) Such inflation is costly and gives incentives to perform structural policy measures (reduce debt, etc.). If a country have bad structural performance and high inflation, it will gain from joining a monetary union with a low-inflation country in terms of inflation going down. However, this reduces the incentives for structural reform! (This point I made specifically in terms of debt in the 1994 paper Loss of Monetary Discretion in a Simple Dynamic Policy Game, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 18, 763-779.) The implications of these simple mechanisms are, as described in the paper:

“We show first that structural distortions in the high-inflation country will be worse—all things equal—under monetary unification than with independent monetary policymaking. This is because the lower inflation rate under a union reduces the incentive of the government of the distorted economy to conduct structural adjustment. Then, we turn to the interplay between endogenous structural reform and the timing of monetary unification. Under reversibility, the high-inflation country will at some point in time undergo a one-time adjustment so as to meet the requirement for entering the union. This entry requirement, endogenously determined by the existing union members, is formulated in terms of the level of structural distortions of the high-inflation country. After entry, structural distortions remain unchanged for a while, as further adjustment is too costly, while structural divergence triggers exclusion from the union.

Under irreversible unification, entry into the union will also take place after a onetime adjustment. However, in contrast to reversible unification, the adjustment is followed by structural divergence because the threat of being expelled at a later date is absent under irreversibility. The government of the new union member can therefore reap the gains of lower inflation without having to suffer the losses associated with structural adjustment. Because the initial union members suffer from such divergence, they are likely to impose a stricter entrance criterion under irreversible than under reversible unification. This tends to postpone irreversible unification relative to reversible unification.” (pp. 418-419)

We further emphasized the public debt aspect by:

“Of course, the actual EMU entry requirements are formulated in terms of observable variables such as inflation and budgetary performance, rather than the underlying structural distortions. However, given the problems of observability and quantification, in practice, it would be difficult to formally apply the latter as a criterion. Nevertheless, because structural distortions are harmful for output, one would expect them to lead to higher inflation and a worse budgetary performance, for example.” (p. 420)

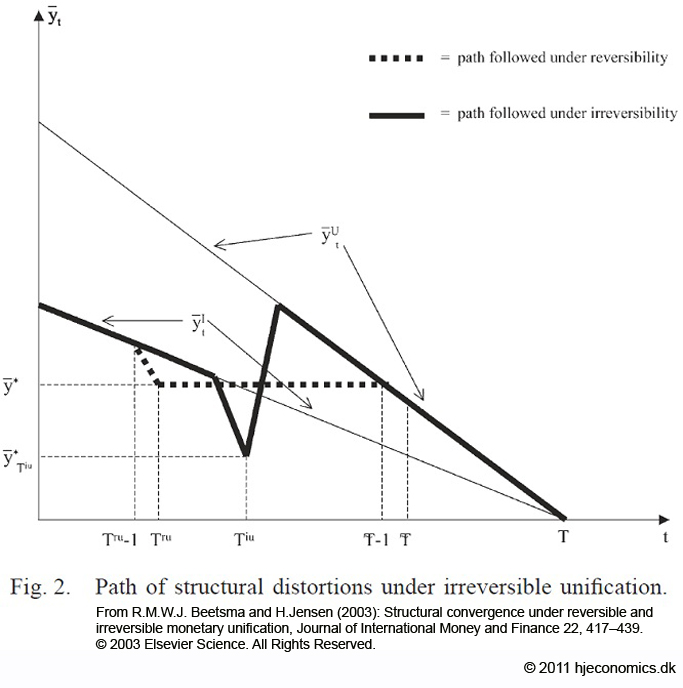

These explanations are then modeled in a dynamic game, and the subgame-perfect Nash equilibrium under both “reversible” and “irreversible” unification are illustrated in the paper’s Figure 2:

Here, the y-axis is the measure of structural distortions in the country with relatively bad structural performance. If it was always outside a monetary union, its structural distortions would follow the lowest downward-sloping line labelled yI (with two arrows pointing to the line). If it was always inside a monetary union, its structural distortions follow the highest downward-sloping line labelled yU (with two arrows pointing to the line). This shows the result that being in a union lowers the incentive for structural reform policies; yU>yI always. Note also that the model has optimistic long-run predictions in the sense that structural distortions vanish at t=T. This was just for computational ease and follows from an assumption about exogenous reductions in distortions over time. The interesting is the endogenous developments in structural distortions, and they should be unchanged by this assumption.

The figure highlights the endogeneity of structural reform when formation of a union, and the timing of the formation, is endogenous. Under reversible unification, there will be an entry requirement y*, and the country meet that at some date Tru. From then on, see the dotted line, there will be no change in structures for a while: Further reform is too costly (remember that the country would, if it was certain to stay in the union, like to slack up to yU), and less reforms, y>y*, leads to exclusion from the union, which is costly in terms of inflation. Under an irreversible unification, as we imagined an EMU to be, at least relative to a fixed exchange rate regime, things are dramatically different: The entry requirement is stricter, y*Tiu<y*, and as a result, formation happens later (Tiu>Tru). But when the union is formed, the country with structural problems “relaxes,” and let structural problems be structural problems. See the bold line. There will be structural divergence. The country “free-rides” on the lower inflation imported from the being in the union, and its incentives to take the costs of structural policies, say, fiscal consolidation, are weakened.

So what would one have said in 1998 when reading this paper? Something along the lines of “The formation of the EMU will pave the way for structural divergence among member countries. In fiscal terms this means that those countries who have undergone fiscal adjustments to meet (or almost meet) the entry requirements, will stop or maybe even reverse the fiscal process when inside the union.”

To most at that time, it was considered a way too far-reaching theoretical exercise. In light of recent events, I should perhaps follow many of those who claimed to have predicted the financial crises and refer to myself as “among those of us who predicted the European debt crisis”? Nah, I better stick with my mantra. But I still believe that Roel and I made a few valid points there in the late 1990s.