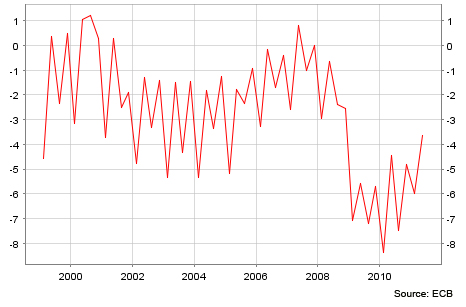

The new “Fiscal Compact” of the European Union is now ready to be signed. The purpose of the compact is to strengthen fiscal discipline among member countries (at least those who sign). The desire for enhancing discipline is obviously triggered by the debt crises felt by many EU countries recently. It is, however, still an open question to which extent the current debt performance is due to the global recession or prior fiscal indiscipline. As debt is cumulated deficits it is hard to separate these matters. As seen in the data, it is nevertheless clear that the crisis itself is associated with a substantial worsening of the average government deficit relative to GDP (numbers are for EU-17):

The issue is then whether deficits before were too big—at the average level they are not dramatically big, but the average, of course, hides some with worse and some with better performance. And those with worse performance may need some discipline, as lack of discipline has negative externalities on other countries (in the monetary union).

The issue is then whether deficits before were too big—at the average level they are not dramatically big, but the average, of course, hides some with worse and some with better performance. And those with worse performance may need some discipline, as lack of discipline has negative externalities on other countries (in the monetary union).

But didn’t the EU already have a Stability and Growth Pact with an excessive debt procedure that opened up for monetary punishment of countries whose deficit exceeded 3% of GDP and/or debt exceeded 60% of GDP? Well, yes, but obviously those laws were not really used (perhaps, and just perhaps, because one of the first countries to violate the Pact was Germany?). And laws and treaties on which you agree, but do not enforce, tend to lose their meaning.

Hence, in the midst of the debt crises, European politicians felt they had to do something. So this new Fiscal Compact was negotiated. Reading this “TREATY ON STABILITY, COORDINATION AND GOVERNANCE IN THE ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION” (pdf here) gave me that strange feeling of Déjà Vu—that sensation so eloquently explained, and dramatically experienced, by Michael Palin in the Monthy Python sketch above. The Treaty offers really not much substantially new compared to what is already in place. Perhaps saying the same things twice is believed to make up for past times’ lack of discipline in EU governance (there, lack of discipline or indecisiveness is indisputable as I see it).

Actually, the new Treaty is in economic terms broadly identical to existing rules (it makes ample reference to the existing excessive deficit procedure) One new element, is a peculiar “Balanced Budget Rule”, which is a misnomer if there ever was one. It stipulates that the structural balance of every governments must not exceed -0.5% of GDP, unless exceptional circumstances occur. Now, what is “structural balance”? The Treaty states:

” ‘annual structural balance of the general government’ refers to the annual cyclically-adjusted balance net of one-off and temporary measures. ‘Exceptional circumstances’ refer to the case of an unusual event outside the control of the Contracting Party concerned which has a major impact on the financial position of the general government or to periods of severe economic downturn as defined in the revised Stability and Growth Pact, provided that the temporary deviation of the Contracting Party concerned does not endanger fiscal sustainability in the medium term” (Article 3(3))

It is therefore not a balanced budget requirement (budgets can fluctuate within flexible bounds as under the old rules), and it introduces a new measure which will be prone to interpretation and endless debates. “Cyclically adjusted”? We know there are million methods to measure that, and the Treaty does not acknowledge that such a measure, will be time varying and country dependent (maybe they will use ECOFIN’s measure, but that doesn’t cause less speculation). Referring to the figure above, I can understand that the Commission’s intention is to push up the average of the whole curve, but you hardly accomplish that by introducing an immeasurable concept. And by naming it a “balanced budget rule” it will make it quite difficult to “sell” to those who are skeptic towards budget rules in general.

The Treaty also focuses on the need for more policy coordination. It states

“. . . the Contracting Parties shall take the necessary actions and measures in all the domains which are essential to the good functioning of the euro area in pursuit of the objectives of fostering competitiveness, promoting employment, contributing further to the sustainability of public finances and reinforcing financial stability” (Article 9)

A lot of positive words, but the numerical rules on which the compact is based, have not anything to do with policy coordination. Only in very simple setups would a (credible) numerical bound on a variable represent a truly coordinated outcome. Generally, it is a way of saying “every country for themselves”. The Treaty even seems to encourage whistle blowing by this weird paragraph:

“If, on the basis of its own assessment or of an assessment by the European Commission, a Contracting Party considers that another Contracting Party has not taken the necessary measures to comply with the judgment of the Court of Justice referred to in paragraph 1, it may bring the case before the Court of Justice” (Article 11(2))

In terms of policy coordination the “Fiscal Compact” is extremely unambitious. What would be needed to coordinate, is a fiscal transfer system that insures member states against asymmetric shocks (Big symmetric shocks which cause fiscal problems for all presumably mean that all countries pay a fine to each other; cf. the quoted Article 3(3).) Such transfer mechanisms work fairly well in other monetary unions like those among American states, Danish municipalities, and so on. But politically that would probably have been too difficult to achieve. Instead one is left with a mild rehash of the old system.

In sum, if you are a skeptic concerning fiscal rules within the EU, this Treaty does not offer significantly any more fiscal restraint that was already there in the first place (in letter, not in reality). It furthermore adds additional room for interpretation, which more than makes up for the now so-called automated punishment procedures in case a country (perhaps) violates the rules.