Paul Krugman is a very active blogger. Almost every time he writes a post on his New York Times blog, there are several comments made around the economic blogosphere. And sometimes Krugman will respond to a few of the comments made, and then it sets off further comments, and so on. It is a Krugman Blog Multiplier. I posit that it needs no formal empirical evidence to establish that it is way above 1. Way above. In this New Year’s post I’ll show a recent example, and argue why this multiplier is too high, and why one should not always “exploit” large multipliers.

Probably one of the issues on which Krugman has been blogging most intensively, is the need for fiscal expansion in the US during the current recession. As his blog is targeted a wider, and non-economically trained, audience, repetition becomes unavoidable (and a presidential election is lurking around the corner). But along with repetition and the urge to politicize, comes a tendency to attack and target those who argue against fiscal spending. Here is the latest example:

In a December 26 post on how “freshwater” economists presumably don’t understand “their own doctrines” (yes, Krugman does continue to group economists into tightly defined categories; a sure sign of politicization), it is his fellow Nobel Prize recipient Robert E. Lucas who is the target. In a luncheon speech at a Council on Foreign Relations Symposium back in March 2009 (!), Lucas said in relation to fiscal stimulus:

“If the government builds a bridge, and then the Fed prints up some money to pay the bridge builders, that’s just a monetary policy. We don’t need the bridge to do that. We can print up the same amount of money and buy anything with it. So, the only part of the stimulus package that’s stimulating is the monetary part.

…

But, if we do build the bridge by taking tax money away from somebody else, and using that to pay the bridge builder — the guys who work on the bridge — then it’s just a wash. It has no first-starter effect. There’s no reason to expect any stimulation. And, in some sense, there’s nothing to apply a multiplier to. (Laughs.) You apply a multiplier to the bridge builders, then you’ve got to apply the same multiplier with a minus sign to the people you taxed to build the bridge. And then taxing them later isn’t going to help, we know that.”

You can even see and hear it for yourself (Lucas starts at around 7:30):

To Krugman, this proves that Lucas does not understand the Ricardian Equivalence theorem, but nevertheless uses the theorem to discard the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus.

This set off a number of blogging responses around the world. Among them, David Andolfatto asks whether Krugman actually understands Ricardian Equivalence? (And he has links to several other bloggers’ responses.) Then Krugman re-posts accusing Andolfatto for not being able to “read straight.” And the blogging continues. The multiplier is huge.

Let me first comment on contents, then on the Blog Multiplier. Everything starts from the Lucas quote. A few statements from a rather informal speech as far as I can see. As I read the first part, Lucas doesn’t think government spending has an effect. He thinks the government spending multiplier is zero, and if there was to be an effect, it comes from the associated monetary policy. The argument is muddy at best. The second part has a gist, but just a gist, of Ricardian Equivalence to it. Now government spending is financed by taxes. And he still thinks that the impact effect of spending is zero. I.e., he believes that the famous balanced-budget multiplier is zero (and not 1). Obviously, in an intertemporal perspective future taxation would not make a difference. Clearly that has a Ricardian Equivalence flavor (timing of taxation is irrelevant), but this is not Lucas’ argument against the zero multiplier. That argument is just not stated. He does not explain why the balanced budget multiplier is zero. So, I think Krugman is barking up the wrong tree.

To make it perfectly clear, I think both Lucas and Krugman knows very well what the Ricardian Equivalence Theorem says and does not say. Andolfatto gives a nice exposition of the Theorem in his post (I tried the same earlier this year when a similar round of posting was in effect): It does not say anything about spending effectiveness. Every trained economist knows that and we don’t have to resort to interviews with Robert Barro to get it sorted out. He wrote a paper about in Journal of Political Economy back in 1974. Go dig it up!

So is there anything wrong with this? Is it really bad that prominent economists spend time on the internet accusing each other for ignorance? I think so. For a number of reasons. What originally starts as a political statement (with personal ingredients as I suspect Krugman is essentially mad at Lucas for bashing Christina Romer’s fiscal multiplier computations), suddenly appears to be revealing a profound scientific disagreement about basic concepts within economics. But this is not the case! It just blurs a valid argument about empirics: How large is the fiscal multiplier? It blurs serious discussions about the right thing to do: Should we have expansive fiscal policy? These are the two central issues. The issues people should be writing about. Bashing each other for not having understood a Theorem is just highly counterproductive.

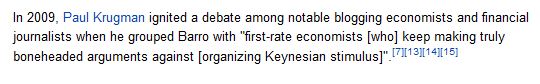

And I believe it is particularly counterproductive when it is Paul Krugman who ignites these discussions. He is a Nobel Laureate, and that gives his words a huge impact. In a recent post he mentioned that he did not like it when economists are”pulling rank“, and I have never seen him doing that. But other people “pull his rank” and use his, often politicized, writings in academic discussions. I am probably not the only one that has to explain students that Krugman blog posts are not valid references for anything. And they stunningly exclaim: “But he has a Nobel?”. Moreover, Wikipedia also gets filled with nonsense lifted off famous economists’ internet musings. This picture is a screenshot of the Wikipedia article on “Ricardian equivalence” (a picture it should be, the article could say something different tomorrow):

This is why Wikipedia never becomes a bona fide academic reference (all the Footnotes are to various blog posts). How relevant is that information to the subject at hand? It is truly a “wash”! So when one has such a big Blog Multiplier, one should consider whether one should exploit it so often. One’s debt level could become unsustainable.

This is why Wikipedia never becomes a bona fide academic reference (all the Footnotes are to various blog posts). How relevant is that information to the subject at hand? It is truly a “wash”! So when one has such a big Blog Multiplier, one should consider whether one should exploit it so often. One’s debt level could become unsustainable.

So, my hope for the New Year is that bloggers everywhere will put more weight on quality and less weight on quantity. Also I hope that those with high ranks take their ranks seriously, and think one more time before starting a wave of blog posts. The example shown here demonstrates how one economist reads something into another economist’s informal talking, and then sets off series of inefficient uses of resources (thiswhich must then include this post, but it is written in my spare time). Talk serious economics instead, since that is your trade. Be formal (which doesn’t necessitates math). To express it differently, here is one of my all-time favorite quotes; incidentally by Paul Krugman:

“. . . just talking plausibly about economics is not the same as having a real understanding; for that you need crisp, tightly argued models.” (Pop Internationalism, Ch. 7, The MIT Press, 1996)

This is a simple, and yet deep, credo, which I think one should adhere to. Quite admirably, Krugman repeats it, in other words, in a blog post of today (which I now multiply). And on this, for me, happy note, I wish you all, wherever you are, a very Happy New Year!